|

|

Membership Services General Info Financial Info Activities Awards Coordinators Director's Info Members' Info Policies Forms Publications Official Publications Director's Publications Ask Dr. SETI ® Fiction Non-Fiction Reviews Reading Lists Technical Support Systems Antennas Amplifiers Receivers Accessories Hardware Software Press Relations Fact Sheets Local Contacts Editorials Press Releases Photo Gallery Newsletters Internet Svcs |

|

Tune In The Universe! by SETI League executive director Dr. H. Paul Shuch Excerpt: The Moon is a Harsh Mirror

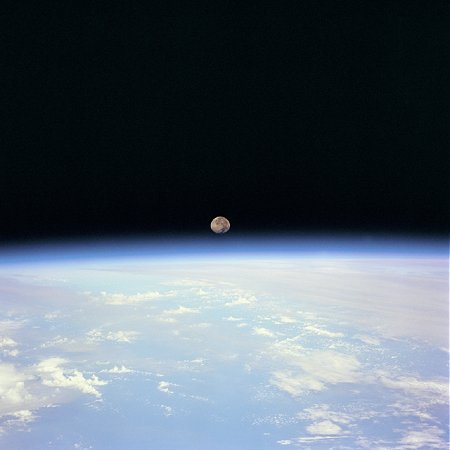

Radio amateurs can take great pride in being at the cutting edge of telecommunications technology. That includes their early contributions to the field of satellite communications, a discipline born in 1945 with the publication in Wireless World of Arthur C. Clarke's pioneering article Extraterrestrial Relays (memorialized in this song). But decades before Amsat (the Radio Amateur Satellite Corporation) was founded, years before Project OSCAR (Orbiting Satellite Carrying Amateur Radio) launched the world's first non-government orbital beacon, even before the birth of the space age, back in the hollow-state era, there was the moon.

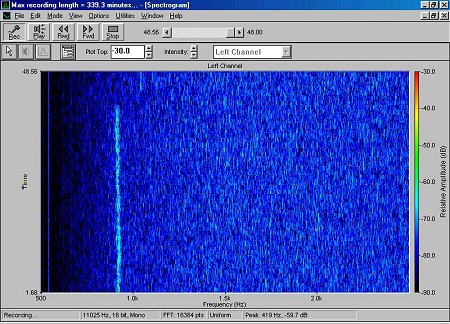

Here's what an EME signal looks like on the computer screen of a Project Argus station:

Never mind that Selene's silver smile masks a rough surface which reflects a scant seven percent of the radiant energy striking it. No matter that the quarter of a million mile path in each direction reduces even the strongest of microwave beams to a whisper lurking beneath the level of the cosmic static. And be not deterred by the rotation of the spheres, which spins the signal frequency off across the receiver dial. No, the challenge was to be the first to talk to another ham a continent away, via the long path off the moon. I was not one to rise to the challenge. In 1960 when the memorable first EME contact was made (by my New England idol Sam Harris, W1FZJ, then the VHF column editor for QST Magazine, and my neighbors at the EIMAC Amateur Radio Club in San Carlos CA), I was a high school student still trying to get my code speed up to take the ham test. I did so by bootlegging on the low end of 80 meters, but that's another story for another chapter. I still cherish the QST cover announcing that first successful EME contact, for success was sought and the battle fought on my favorite of all ham radio frequencies, 1296 MHz, at the bottom of the microwave region. When I was finally ready to make my own footprints on the moon a decade later, I chose the lower spectrum of the popular 2-meter ham band, where equipment was more readily available and the free-space path loss a tad more manageable. It was on 2 meters that I had a memorable almost-first-contact. Now bear with me, please, if I get technical for a minute, because I want to tell you about the equipment we used in those days. If you're not a techie, feel free to skip to the next paragraph. My neighbor Mike Staal K6MYC was already actively bouncing 2-meter signals off the moon with his160-element Cush-Craft collinear array, a Big Gun in anybody's book, and he was my mentor. I had built the Plumber's Delight transmitter from the ARRL Handbook (a pair of 4CX250's in push-pull) driven by an Ameco 6'n'2 transmitter on CW. I got 700 Watts output, through RG-17, to four Oliver Swan 12-element Yagis on 12-foot booms, spaced two wavelengths vertically and horizontally on a jury-rigged H-frame. My azimuth rotor was a Ham-M, and my elevation rotor was taken off an old clothes drier. The counterweight was a piston from my old 1956 Chevy. The receiver was an early solid-state preamplifier (2 dB noise figure) and the popular W2AZL vacuum-tube receive converter into a military surplus RME receiver at 10 meters. All pretty crude stuff by today's standards. But was I ever excited! So much for the station. I had just lashed the mess together, pointed toward the moon, and immediately started hearing weak Morse code on 144.010 MHz. I fell into 2-minute sequences, listened and called, listened and called, and after nearly an hour had pieced together all the elements necessary to constitute a contact. Not able to contain my excitement, I called up my mentor, and blurted out, "Guess what, Mickey, I just made my first EME two-way!" "Congratulations," Staal replied. "Who'd you work?" "WA2DFO," I replied excitedly. "Congratulations," my neighbor repeated to my puzzlement, then added, "you just made your first almost contact -- with VE2DFO. Learn the callsigns of the guys on the band. It gives you a 3 dB advantage." Four decades later, and just a little bit up the band from the very first EME contact, I now seek even fainter signals not reflected off the moon, but transmitted across the interstellar gulf. The techniques pioneered by the early moonbouncers are my stock in SETI trade. And in trying to intuit how ET might think, we are once again seeking that 3 dB advantage.

|